Continuous Random Distribution Biased Toward Particular Number

UPDATE: I've posted a related article here.

When building simulations of real-world phenomena, or when generating test data for algorithms that will be consuming information from the real world, it is often highly desirable to produce pseudo-random data that conform to some non-uniform probability distribution.

But perhaps I have already lost some readers who do not remember STATS 101 all those years ago. I sure don't. Let's take a step back.

The .NET Framework conveniently provides you with a pseudo-random number generator that produces an approximately uniform distribution.[1. The set of real values representable by doubles is not uniformly distributed, and the Random class is not documented as producing a uniform distribution. But in practice it is a reasonable approximation.]

By a "uniform distribution" we mean that if you took a whole lot of those random numbers and put them in two buckets, based on whether they were greater than one half or smaller than one half, then you would expect to see roughly half the numbers in each bucket; there is no bias towards either side. But moreover: if you took those same numbers and put them in ten buckets, based on whether they were in the range 0.0-0.1, 0.1-0.2, 0.2-0.3, and so on, you would also expect to see no particular bias towards any of those buckets either. In fact, no matter how many buckets of uniform size you make, if you have a large enough sample of random numbers then each bucket will end up with approximately the same number of items in it.

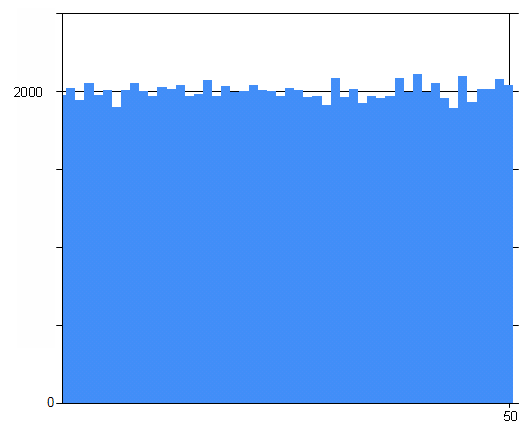

That's what we mean by a "uniform probability distribution": the number of items you find in the bucket is proportional to the size of the bucket, and has nothing to do with the position of the bucket. Here I've generated one hundred thousand pseudo-random numbers between zero and one, put them into fifty buckets, and graphed the number of items found in each bucket.[2. Using the awesome Microsoft Chart Control, which now ships with the CLR. It was previously only available as a separate download.]

Such a graph is called a histogram. As you can see, each of the 50 buckets contains approximately 2% of the total, and there seems to be no particular pattern to which buckets were lucky enough to get a few more than average. This histogram is entirely characteristic of a uniform distribution.

Now let's consider for a moment the relationship between the geometry and probability. Suppose we chose one of those data at random, from the hundred thousand points. What is the probability that it was in bucket 25? Obviously, the "height" of that bucket on the graph divided by the total number of items. But geometrically, we could think of this probability as the area under the curve limited to the region of bucket 25 divided by the total blue area.

Do you notice something vexing about this graph though? The axes are completely determined by the arbitrary factors that I chose in running my simulation. Let's normalize this. We'll re-label the horizontal axis so that it represents the highest value that would have been put in that bucket. How shall we re-label the vertical axis? Well, we said that the probability of a particular datum being found in a particular bucket was proportional to the area of that bucket. Therefore, let's recalibrate the axis such that the total blue area is 100%. That way, the answer to "what is the probability of a given item being found in such and such a region?" is precisely the area of that region:

This normalization has the beautiful property that no matter how many random numbers we generate, and no matter how many buckets we put them in, every histogram will look more or less the same, and will have the same labels on the axes; the distribution will go from zero to one on both axes and the total area will always be 100%.

Now imagine what would happen in the limiting case. Suppose we kept generating more and more numbers; trillions of them. And we made the buckets smaller and smaller. If you squint a bit, you might as well just say that you're going to do a graph as though the whole thing were continuous, and just draw the extraordinarily simple line graph:

And there you have it; the continuous uniform distribution. But that is certainly not the only distribution! There is the famous "bell curve" or "normal" distribution. The range of the normal distribution is infinite on both ends; a normally-distributed random value can have any magnitude positive or negative. Here's Wikipedia's image of four different bell curves:

Remember, these are just the limiting case of a histogram with a huge number of buckets and a huge number of samples. With these distributions, again, the probability of a value being found in a particular range is proportional to the area under the curve in that range. And of course, the area under each one is the same — 100% — which is why the skinny bell is so much taller than the wide one. And notice also how the vast majority of the area is very, very close to the peak in every case. The normal distribution is a "thin, long tail" distribution.

There are other distributions as well. For example, the Cauchy distribution also has the characteristic bell shape, but its tail is a bit "fatter" than the normal distribution. Here, again from Wikipedia we have four Cauchy distributions:

Notice how much fatter those tails are, and how the "bell" correspondingly has to be narrower to ensure that the area still adds up to 100%.

You know something that is still a bit odd about these graphs though? Because the probability is proportional to the area under the curve, the actual value of the curve at any given point isn't really that meaningful. Another way to characterize a probability distribution is to work out the probability of a given number or any number less than it being chosen; that is the area under the curve to the left of that number. Of course, the area under the curve is simply the integral, so let's graph the integral. We know that such a curve is going to increase monitonically from a limit on the left of zero to a limit on the right of one, since the probability of getting any very, very small number is close to zero, and the probability of getting any number smaller than a very large number is close to 100%. If we graph the integral of these four Cauchy distributions we get:

That graph is called the cumulative distribution and notice how it is extremely easy to read! Consider the purple line; clearly the probability of getting a value of two or less is about 85%; we can just read it right off. This graph has exactly the same information content as the "histogram limit" probability distribution; its just a bit easier to read. It is quite difficult to tell from reading the original graph that about 85% of the area under the curve is to the left of the 2.

Apropos of nothing in particular, I note that we have a function here that is monotone increasing; that means that we can invert it. Let's swap the x and y axes:

This function — the inverse of the integral of the probability distribution — is called the quantile function. It tell you "given a probability p from zero to one, what is the number x such that the probability of getting a number less than x is equal to p?" That graph should look familiar to anyone who has taken high school trig; the quantile function of the Cauchy distribution is simply the tangent function rejiggered to go from zero to one instead of -π / 2 to π / 2.

So that's pretty neat; the Cauchy bell-shaped curve is in fact just the derivative of the arctangent! But so what? How is this relevant?

We started this fabulous adventure by saying that sometimes you want to generate numbers that are random but not uniform. The graph above transforms uniformly-distributed random numbers into Cauchy-distributed random numbers. It is amazing, but true! Check it out:

private static Random random = new Random(); private static IEnumerable<double> UniformDistribution() { while (true) yield return random.NextDouble(); } private static double CauchyQuantile(double p) { return Math.Tan(Math.PI * (p - 0.5)); } private static int[] CreateHistogram( IEnumerable<double> data, int buckets, double min, double max) { int[] results = new int[buckets]; double multiplier = buckets / (max - min); foreach (double datum in data) { double index = (datum - min) * multiplier; if (0.0 <= index && index < buckets) results[(int)index] += 1; } return results; } and now you can tie the whole thing together with:

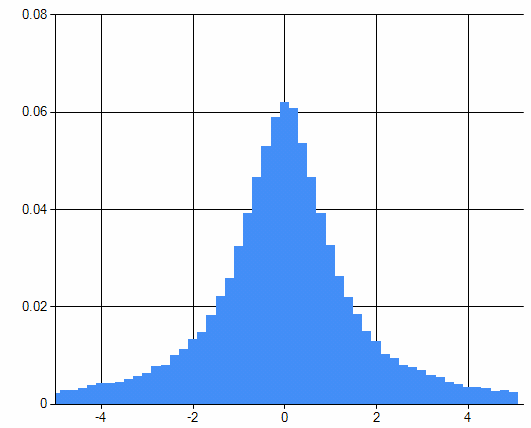

var cauchy = from x in UniformDistribution() select CauchyQuantile(x); int[] histogram = CreateHistogram(cauchy.Take(100000), 50, -5.0, 5.0);

And if you graph the histogram, sure enough, you get a Cauchy distribution:

So, summing up: if you need random numbers that are distributed according to some distribution, all you have to do is

- Work out the desired probability distribution function such that the area under a portion of the curve is equal to the probability of a value being randomly generated in that range.

- Integrate the probability distribution to determine the cumulative distribution.

- Invert the cumulative distribution to get the quantile function.

- Transform your uniformly distributed random data by running it through the quantile function.

Piece of cake!

Next time: a simple puzzle based on an error I made while writing the code above.

Source: https://ericlippert.com/2012/02/21/generating-random-non-uniform-data/

0 Response to "Continuous Random Distribution Biased Toward Particular Number"

Publicar un comentario