Which App on My Tablet Will Read Me a Book Aloud

Since the invention of the tv set, a box you lot could put a child in front of and leave them passively entertained, naught has changed how children spend their time as much equally the tablet figurer.

4 years agone, simply 7% of 5- to 15-yr-olds in the UK had access to a tablet. Past last year it was 71%. Some 34% of this age group even owned the tablets themselves, as well as 11% of 3- to 4-year-olds, according to Ofcom figures.

But the popularity of tablets among children is a controversial topic. Are these devices – with their apps, games and access to online video – distracting children from more traditional, some might say more wholesome, activities, such equally reading?

In my work life, I regularly write well-nigh the beneficial aspects of digital play, complementing books and concrete exercise rather than replacing them. But as a parent of a six-year-former and an eight-year-one-time, I worry virtually the comments suggesting – with varying degrees of politeness – that devices and apps are sending our children to illiteracy hell in a digital handcart. What if those people are correct?

How have children'south reading habits inverse over the concluding five years since the launch of Apple tree's first iPad in 2010 – and can the growth in their digital habits be linked to a fall in reading?

Reading on the rise?

Effectually two fifths of immature British children read every day. Ofcom found that twoscore% of 5- to 7-year-olds and 39% of 8- to 11-year-olds read magazines, comics or books almost every mean solar day, in its 2014 Children and Parents: Media Use and Attitudes report.

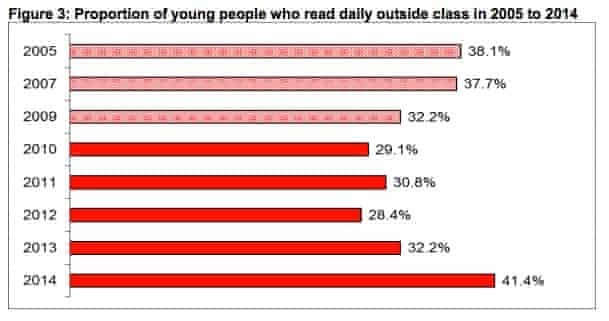

The UK's National Literacy Trust (NLT)'s Children'south and Immature People'due south Reading in 2014 study offers a similar statistic, noting that the percentage of viii- to eighteen year-olds reading daily outside class was 41.4% in 2014 - up from 29.1% in 2010.

By contrast, Publisher Scholastic publishes a biannual Kids & Family Reading Report covering American children'south reading habits. Its latest edition suggests the pct of US 6- to 17-year-olds reading books for fun v-7 days a week fell from 37% in 2010 to 34% in 2012, then 31% in 2014.

Conspicuously at that place is no consensus.

Focus on focusing

Joanna de Guia recently closed her contained children'due south bookshop in Hackney to launch Story Habit, which runs author events, school workshops and "literature walks" to encourage children to read for fun.

"I'm afraid I'thousand going to go political well-nigh this," she says. "Reading for pleasure has always been cornered past the middle- and upper-center classes, although historically at that place's likewise been a very cocky-determined, self-educated working form group who've also had a tradition of reading for pleasance and understanding how important information technology is."

De Guia believes that this tradition has been "chipped away at" in recent decades, and as a critic of the phonics system used to teach early reading skills in schools, she is concerned that reading may seem like a chore to many children.

"If you come up from a family where you lot go domicile and read a story at night, and associate reading with lovely fourth dimension with your parents, the fact that you do this slow-equally-ditchwater matter at school is immaterial," says de Guia.

"Only if you practise no reading at dwelling, then go to school and are forced to do this dull thing with no idea really why you're doing it other than 'information technology's something you've got to practise', and then it'southward totally going to put you off. We interfere: 'You lot have to read. Y'all have to read THIS'. There's zero more guaranteed to put a child off something."

Where does technology fit in to this? De Guia is concerned that with games, apps and videos, tablets provide too many distractions from longer-course reading.

"You don't get that opportunity to just sit and immerse yourself in a story from start to end. That'due south brilliant for concentration, and, chiefly, it creates a context for the idea of narrative. The amount of concentration required on any digital device is very short," she says.

"So, reading for pleasure is non being supported by our educational curriculum, and at that place'southward the prevalence of these new toys-slash-tools [tablets]. And they conspire to create very short attention spans, and children who desire instant gratification."

"If they're not getting that instant gratification from the book they're reading, they can just play a game instead. So what happens to the story? I worry nigh a generation of children who don't want to know what the end of the story is, because that's how we brand sense of the globe."

Screens and reading

Tablets every bit distractions from reading through other forms of amusement is one thing. But what nigh digital reading on these devices? Tin can inventive apps and absorbing ebooks fuel children'southward desire to know what the end of the story is? Could they even have some advantages over print reading?

This is where you plunge into a world of academic research studies that tin leave you with more questions than answers.

There are studies suggesting that reading digitally is worse for recall and comprehension than reading books – yet many of them are based on estimator screens not touchscreen tablets, and involved adults who'd grown up reading books, not children who've been swiping on tablets since they were toddlers.

There are studies suggesting that reading digitally may, in fact, do good certain groups of children, from boys from disadvantaged backgrounds who struggle with print, through to children with dyslexia – but many of these are based on small sample groups, with the mutual determination being that more research is needed.

"Nosotros need newer research, larger-calibration research and a younger cohort," says NLT project managing director Irene Picton. "We're really dandy to look at how technology could be used to positively back up less confident parents in sharing books and stories with their children, for example. A really good app or website could be a forcefulness for proficient in that situation."

"Virtually everything most e-reading is preliminary or small-scale at this point," agrees David Kleeman, senior vice president of global trends at inquiry firm Dubit.

Kleeman makes another of import signal, though, which is that children are reading fifty-fifty when they are not explicitly reading ebooks or volume-apps on their devices.

"Information technology is hard to tell what 'reading' is today: we're not really measuring the amount of content that kids are reading incidentally within games and apps," he says, suggesting that "screen time is no longer a viable term" because children are doing then many things on those screens, many of which require reading text.

Books on the screen

App developers accept been exploring tablet stories for children since the earliest days of the iPad, and there has been scepticism from the showtime about whether some of these apps aid or hinder the development of reading skills.

Children'due south author Julia Donaldson made headlines in 2011 when she explained why there wasn't an official app for The Gruffalo:

"The publishers showed me an ebook of Alice in Wonderland. They said, 'Look, you tin can press buttons and practice this and that', and they showed me the folio where Alice'south neck gets longer. There'south a push button the child can press to brand the neck stretch, and I thought, well, if the child'due south doing that, they are non going to be listening or reading, 'I wish my true cat Dinah was here' or whatsoever it says in the text – they're just going to exist fiddling with this wretched button."

Donaldson'due south views carried (and still carry) real clout among publishers and parents akin. But the app in question was one of the early, experimental attempts to effigy out how tablet reading might work for children. There are four years of further experiments and learnings since then, and more to come up.

"We often forget that books are a technology besides, and one that'southward had several centuries to evolve. With ebooks or apps, we're comparing them to a relatively new format for reading. It's important to be open up-minded around this," says Picton.

"Don't forget the suspicion with which Socrates greeted writing. He idea that people wouldn't call up things if they were reading them rather than listening to them. Now we're worried most not remembering things considering nosotros're reading them on a screen not a page."

"We've got an opportunity here with digital reading – ebooks and apps that encourage reading in all its forms – to keep reading relevant. And past existence suspicious of it and proverb it'southward worse than reading on newspaper, we ignore that opportunity."

Kleeman offers what sounds like a more than 2015 accept on Donaldson's warning, though. "With one screen competing for the child'southward attention with every possibility – video, apps, games, books, social apps – information technology'southward very easy to get seduced by possibilities: to throw in bells and whistles that don't support or enhance the story, just distract," he says.

Tablet distractions

Asi Sharabi, co-founder of British startup Lost My Name, which makes personalised (impress) books for children, thinks that tablets may have a deeper, cultural problem with reading as a shared experience between children and parents.

"1 affair that the iPad as a device, every bit a cultural artifact, has never actually been good at are these shared co-reading experiences. Unlike books, where in that location's no option but to sit down down and read information technology with your kid in the early years," he says.

"The tablet took a slightly unlike direction: it became the mod babysitter, or the mod pacifier. That's not necessarily a negative thing, only it's more than near giving the child the device – 'It'southward your iPad fourth dimension now' – rather than sitting downwards to read or play together on it."

Sharabi suspects this may be rooted in how parents have been using television for decades: screen-based entertainment for children is ofttimes a chance for parents to get other things washed.

"It's non just that kids are expecting screens to be noisy and shouty and fun and interactive. Simply also because of our center-class guilt, where we put boundaries around screen fourth dimension and tablet use, when kids go half an hour or an hour with the iPad, they will opt for the things that excite them the most."

Support for this theory can exist institute in a written report called Exploring Play and Creativity in Pre-Schoolers' Use of Apps, which surveyed 2,000 parents and found their favourite children's apps were educational and story apps.

The children'southward top 10 favourite app brands? YouTube, CBeebies, Angry Birds, Peppa'due south Paintbox, Talking Tom, Temple Run, Minecraft, Disney apps, Processed Crush Saga and Toca Boca apps.

Sharabi backs upwardly Kleeman'southward view that story-apps that try to ape those other forms of entertainment may exist fun, only they won't necessarily exist good for reading.

"Getting kids really deeply engaged in a narrative is something that books are very expert at. It'southward the working of the imagination: that time and cognitive space that you need to develop the understanding and empathy with the characters; the plot; the emotion of the book," he says.

"These are all things that interactive storybooks are only not doing well enough. Kids will always wait offset for what they can do next on the screen to trigger some interactivity." A topic that Natalia Kucirkova explored in more depth for the Guardian in Dec 2014.

Books as applied science

Both Sharabi and Picton brand the point that books, equally much as apps, are a form of applied science, with features including being designed for co-reading; capable of being beautiful concrete objects; and capable of being read when the tablet has been put away for the day.

"A book is a beautiful thing if it's produced beautifully, even for children who don't value reading. If information technology'south a desirable matter, they'll want it every bit much as they would desire an iPad or annihilation else," says De Guia. "We just take to get more than clever about how we present real books."

Kate McFarlan, strategic manager at British volume-press company Clays, suggests that, for books, providing a intermission from screens "is a factor welcomed by children besides as parents", and points out that one in iv books sold in the U.k. concluding year were for children, with quality on the rise.

"Nosotros have in the terminal few years started working with three or four new children's publishers, all of which are growing. Their accent is on quality and skilful value, beautiful designs and great finishes," she says.

And parents, carers, teachers or older siblings to read them with. Which is where this whole argue about children, reading and screens comes back to, well, people not technology. And this is a familiar bailiwick in the academic and parenting worlds alike.

Dr Gareth Williams, an skilful in reading development at Nottingham Trent University, fills me in on "The Matthew Effect", for example: a theory that young children who are encouraged to develop their language skills will take to reading more naturally a few years after.

"It's about predicting how good children are at reading and how much they enjoy it when they're older by tracking back the evolution pathway to things similar language development and language play when they're younger," he said.

"So, how confident very young children are with playing around with language helps them when they later brainstorm to engage with print. They already have that foundation."

Williams too cites research indicating that children's reading abilities may exist linked to the prevalence of books in their home, and suggests more than enquiry is needed – that mantra again – into whether there is a similar result if the adults in the household use tablets for reading, including with the children.

Co-reading may be central

"Nosotros recall of books equally being a very solo, private activity, but for young children – pre-readers – books are very much a social activity, whether they're beingness read to in a group, or by a parent," says Williams. "Going forward, can that social and interactive attribute happen with devices every bit well as books? Really it comes down to the people."

Scholastic'due south latest study provides more than fuel for that theory, challenge that factors that predict if 6- to 11-yr-olds will be frequent readers include "having parents who are frequent readers", "reading aloud early on and often", and "spending less fourth dimension online using a estimator".

Information technology's a simultaneously reassuring and worrying concept. Reassuring, because it sidesteps the "are my children playing games not reading on the tablet?" question, if you're reading to/with them when the tablet is turned off.

Worrying, because there's a danger that this boils down to another opportunity for parent-shaming: from frazzled full-time parents to shift-workers to white-collar 60-hours-a-week executives (Amazon staff included), finding quality time for co-reading can be tough.

At that place'due south no easy answer, then: no clear villain on either the engineering or people side of the battle to figure out healthy media habits for children – let alone put them into practice. Although more than than one interviewee pointed to 1 instance of people and technology bringing the worst out of one some other.

"Maybe the trouble with kids and screens is not kids and screens: it'due south parents and screens," says one, privately. "Children wait to us equally function models, so how can nosotros await them to honey reading, if we can't tear ourselves away from Facebook or WhatsApp for ten minutes to read with them?"

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2015/aug/24/tablets-apps-harm-help-children-read

0 Response to "Which App on My Tablet Will Read Me a Book Aloud"

Publicar un comentario